- The Kiwi economy is in recession and the outlook is simply weaker, compared to the May budget. Nominal GDP (the tax base) is coming in $20bn (or 1.1%) lower than Budget. That makes the Government’s fiscal position that much harder to manage. Why? Revenue is down because people spend less (GST take) and earn less (PAYE). And higher unemployment rates required benefits.

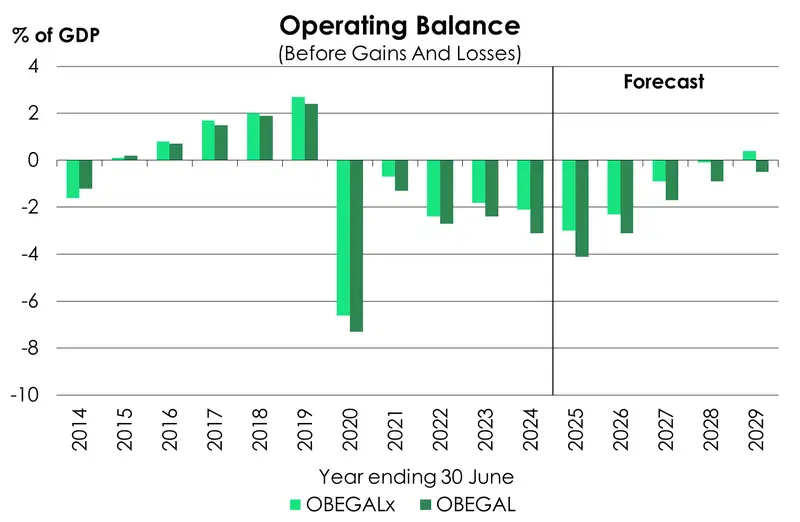

- The Government will record 9 straight years of deficits, worse than post-GFC. But to be fair, Governments did a lot more during Covid.

- We did get a new measure called OBEGALx (sounds like an AI robot with terminator tendencies), that strips out ACC and gets back to surplus in 2028/29.

- But the real story is the reduction in productivity. And the Government is partly to blame here – both sides of Government that is. Why? Because we’ve underinvested in key infrastructure for decades. And that’s strangling our economy. We do applaud the commentary around building a pipeline of infrastructure investment. Time to walk the walk.

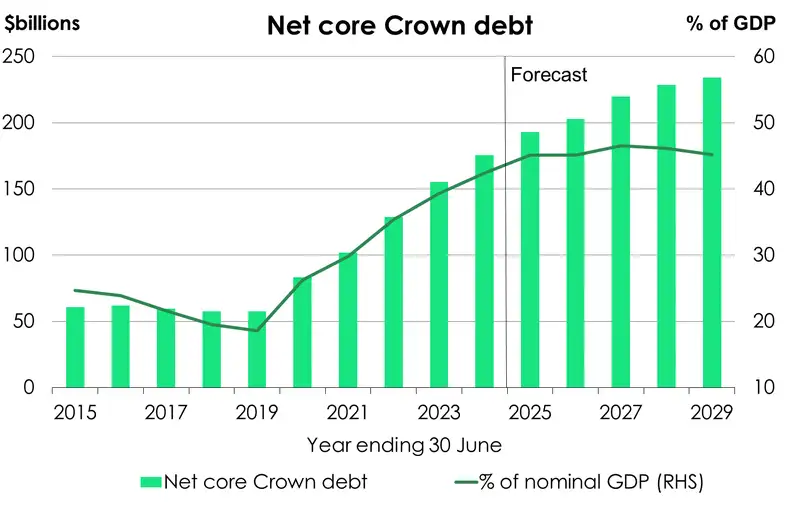

- Wider and more persistent deficits mean more debt. And Treasury issuance is higher over the forecast horizon. We’re not worried, as sovereign debt levels are coming off a very low base, and compare favourably to our offshore peers.

It is hard for the Government, any Government, to balance the books of an economy in recession. And the forecasts have been hamstrung by poor productivity. We’re not getting bang for buck. And we’re not getting back to surplus, anytime soon.

The Budget is being imbalanced by a significant reduction in the forecast tax base (the nominal economy) and an unwelcome lift in benefits (with rising unemployment).

Treasury now forecasts the Kiwi economy to be about $20bn (or 1.1%) smaller than the May budget. A smaller economy generates less tax revenue. GST receipts are below forecast, because people are spending less. Income tax is below forecast, because wage growth is cooling. Corporate tax is below forecast, because company revenues are weaker. And that’s the tax take. Spending is higher than forecast, because benefits are higher with more unemployed. And there’s also more to be spent in other areas, like education, just to meet changing demographics. The ageing population, a sensitive subject, will only make this worse every year into the future.

The return to surplus has been achieved on a technicality. And that is through the introduction of a new fiscal measure coined OBEGAL X. It’s essentially the original measure of OBEGAL but removes ACC revenues and expenditure on the basis that recent ACC deficits have clouded the true OBEGAL. Nonetheless, the return to an OBEGAL X surplus is still further away than it was back at the May Budget. While regular OBEGAL see’s no return to surplus in the forecast horizon. And overall, the weaker reality means more debt. The debt management office will have to issue an additional $20bn beyond 2025 and out to 2028. Net debt rises to 46.5% of GDP and remains above previous projections

For us, the real story is the reduction in productivity. Lower estimates of Kiwi productivity are the leading factor in Treasury’s softer outlook today. Failure to invest in key Infrastructure for decades has strangled us. Yes, the government have re-emphasised their commitment to prioritise a pipeline of infrastructure investment. Which we applaud. But now we need them to walk the walk.

A lack of productivity continues to drag the economy

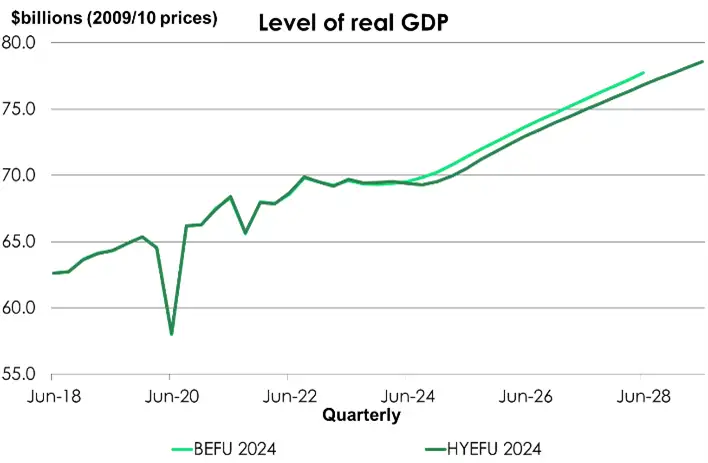

With some forewarning, Treasury once again softened their outlook for the Kiwi economy. Comments from a recent speech by Treasury’s Chief Economic Advisor - Dominick Stephens – hinted at the downgrade to the economic outlook today. The good news is that the Treasury sees the economy growing from the December 2024 quarter. However, it is at a more subdued pace than previously expected. Compared to their forecasts in May, Treasury now expects the economy to average growth of just 0.5% in the 2025 fiscal year compared to the 1.7% laid out in their May forecasts. The markedly revised lower forecasts for real GDP entail a weaker outlook for the nominal economy. Compared to their forecasts in May, Treasury now expects the nominal economy to be nearly $20bn (or 1.1%) smaller by the end of the forecast period. The consequences of which will flow through onto lower tax revenues.

It can seem a bit odd that the economic outlook has been revised lower when rate cuts (and a lot of them) have been delivered earlier than Treasury had initially expected. Normally the delivery of rapid rate cuts would bolster the case for an improved outlook. But in this case, Treasury’s revisions for a weaker economy are rooted in lower estimates of Kiwi productivity – specifically, lower estimates of labour productivity. It’s a point of growing discussion and worry. Back in May, Treasury downgraded its economic outlook because of poor productivity. And like déjà vu, Treasury’s forecasts have weakened for the same reason. Treasury now sees labour productivity averaging at 0.9% compared to the already revised down 1.2% in their prior forecasting round. As a result, potential output is 1% smaller than forecast in the Budget Update in the year to June 2028.

Beyond the size and productivity of the economy, changes to Treasury’s forecasts were most noticeable in their forecasts for unemployment and inflation. Previously Treasury had forecast the unemployment rate reaching a peak of 5.3% by the end of 2024. The labour market however has proven stronger than expected. While the unemployment rate peaks marginally higher at 5.4%, Treasury has pushed out the timing to the middle of 2025. An increasing number of people leaving the labour force, particularly due to a substantial lift in Kiwi departures has delayed the deterioration in the labour market. And anecdotally, Treasury is also hearing from businesses that firms are preferring to hold onto staff, and instead opting for lower wage increases over the time.

At the same time Treasury’s forecasts for inflation were lowered and brought forward. They had to be, given that inflation pressures have come off quicker than expected. Back in May, Treasury hadn’t envisioned a return to the 2% midpoint until June 2026. But inflation has surprised us all on the downside. In the September quarter this year, headline inflation fell to 2.2% helped by chunky falls in tradable inflation. And going forward Treasury now sees further downside risk for further hefty falls in tradable inflation with recent data, particularly lower oil prices, indicating even lower tradable inflation ahead. As such, Treasury now expects headline inflation to drop below 2% in the near term, before stabilising at 2% in the second half of 2025.

The faster delivery of rate cuts and a cooler inflation outlook has also seen Treasury lower their interest rate forecasts. Treasury now sees the 90day interest rate track dip below 4% in the June quarter of next year. Essentially 9 months earlier than previously forecasted.

Deeper deficits

As forewarned, the Treasury’s fiscal outlook has been materially downgraded. The nominal economy is much smaller than previously thought, $20bn smaller to be exact. A smaller nominal economy however means a smaller tax base. And as a result, core Crown tax revenue is $13bn smaller across the five-year forecast horizon compared to the Budge Update. The discrepancy is largely owing to a weaker economic outlook which has reduced forecast GST receipts. That is, it takes longer for the economy to recover from the recession, resulting in a weaker stream of tax receipts for the Government. However, growth in core Crown tax revenue is expected to pick up from the 2026 fiscal year.

On the other side of the ledger, the governments expenditure track has been lifted. Off the back of a weaker economic outlook, core crown expenses are higher in each of the forecast years compared to Budget. The harsher state of the economy brings about rising unemployment. And with it, a rise in expected benefit payments and job seeker support. Treasury forecasts a 12% increase in jobseeker respondents in the fiscal 2024/25 year, which will cost the government $0.6 billion to cover. Thereafter as the economy recovers, the increasing number of jobseekers is set to moderate and incur the government an average cost of $0.2bn per annum. Our aging population is also costing the government. Over the forecast period, the number of superannuation recipients is set to rise to 1,053,000 from todays 899,000. And that is set to cost the government an additional $7.2bn over the forecast horizon.

Piecing it altogether, the Government is expected to run deeper operating deficits. And this is where it gets interesting. Because Finance Minister Nicola Willis has introduced an alternative measure of the operating balance – OBEGALx – which excludes revenue and expenses by ACC. Under either measure however the Government’s books are far weaker than presented in May. OBEGALx returns to a surplus of $1.9bn in the year ending June 2029after first widening a further $18.3bn over the forecast period. Meanwhile under the traditional measure, OBEGAL, the deficit widens by almost $4bn in the current fiscal year. The deficit shrinks over the forecast period, but the books remain in the red with no return to surplus yet to be seen. If the forecast materializes, that’s at least nine years of the Government running a deficit, three years longer than post-GFC.

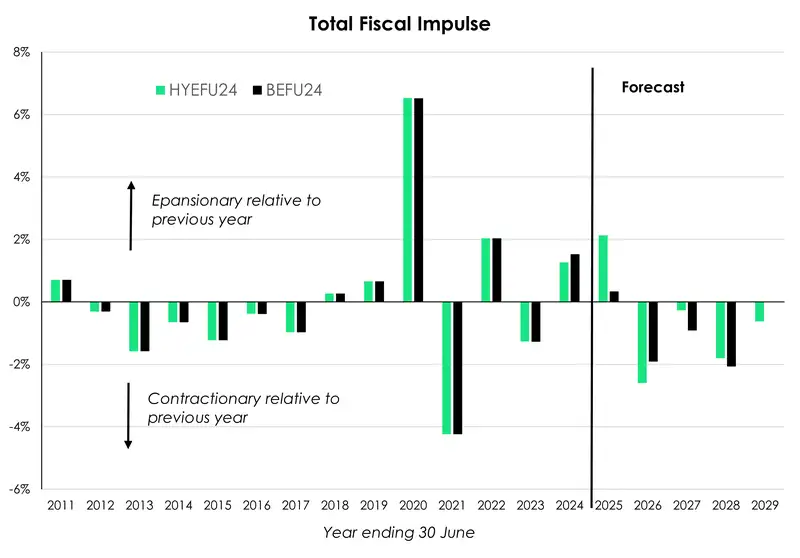

Stronger near-term fiscal impulse

Treasury’s fiscal impulse analysis provides a measure of how much fiscal policy is either adding to or taking away from aggregate demand from one year to the next. Overall, fiscal settings are again set to be generally contractionary with Treasury’s fiscal analysis still averaging -0.6% over the entire forecast period - as it was in the Budget Update. However, once again the yearly profile has changed. In 2024/25, fiscal settings have increased from more neutral settings of just 0.3%, to now much more expansionary settings of 2.1%. Meanwhile, settings for 2025/26 have been made more contractionary. Thereafter, fiscal settings remain in contraction but at a shallower rate than previously thought. Ultimately, this means that there could be some more near-term pressure on inflation with fiscal conditions being more expansionary in the fiscal year ahead. But this may be less of a worry for the RBNZ than in recent times, given inflation has returned back within their 1-3% target band and even converged closer to their 2% midpoint range.

A lot more debt, means a lot more issuance

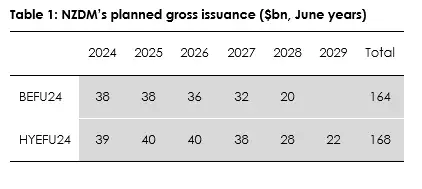

Deeper operating deficits, a smaller forecast tax base, and a wider cash position means a lift in the debt profile. And more debt needed means more issuance. Planned gross issuance was increased – once again – by a chunky $20bn out to the 2028 fiscal year. The 2029 fiscal year was also added to the forecast period, with a $22bn bond programme. The planned issuance profile is below.

All content is general commentary, research and information only and isn’t financial or investment advice. This information doesn’t take into account your objectives, financial situation or needs, and its contents shouldn’t be relied on or used as a basis for entering into any products described in it. The views expressed are those of the authors and are based on information reasonably believed but not warranted to be or remain correct. Any views or information, while given in good faith, aren’t necessarily the views of Kiwibank Limited and are given with an express disclaimer of responsibility. Except where contrary to law, Kiwibank and its related entities aren’t liable for the information and no right of action shall arise or can be taken against any of the authors, Kiwibank Limited or its employees either directly or indirectly as a result of any views expressed from this information.