The risks we face from offshore are to the downside. The homegrown risks we face are to the upside. Imported inflation is easing. Domestic inflation is sticky, with a myriad of forces pushing and pulling. The good news is incomes should outgrow inflation, eventually, bringing a slow end to the cost-of-living crisis.

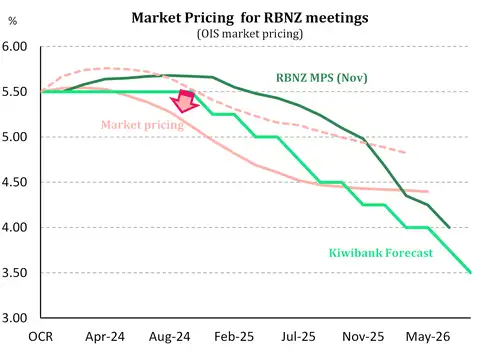

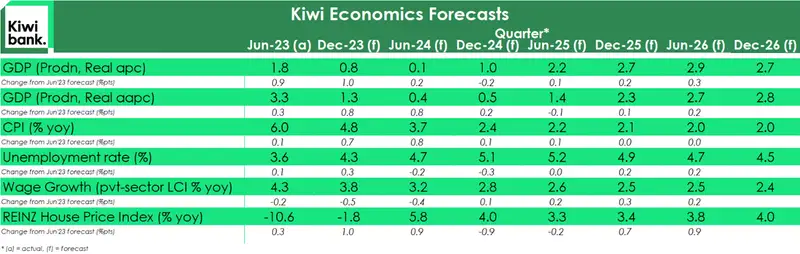

Our forecast terminal cash rate of 5.5% is unchanged. Although the RBNZ’s threatening to do more. Interest rates could back up near term. But we forecast an inevitable decline later in the year. It’s a game of two halves. We expect RBNZ rate cuts from November.

It's that time of the year when we sharpen our pencils, pull out the darts, dust off the crystal ball, and pray to the economic gods. They never answer. But it’s a healthy exercise to step back and refine our view into next year. And we continue to see the current economic climate as particularly awkward for many businesses and households.

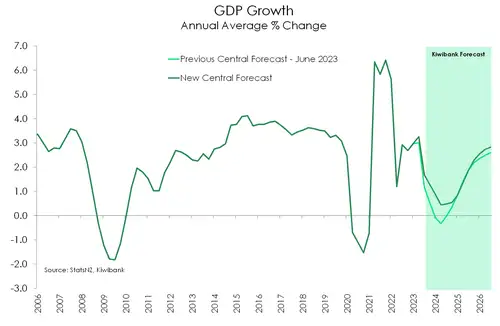

We expect to see a shallow recession, that will feel worse than the migrant-inflated figures suggest. On a per capita (per person) basis, we are likely to record a prolonged contraction. Households will continue to feel the pinch. And businesses will continue to put out fires as order books shrink, costs inhibit, and profitability shrivels. Downbeat employment and investment intentions of many businesses speak volumes. Unemployment will most likely continue to rise, wage growth will cool, and inflation will return to target. It is likely to be something close to the soft landing nirvana touted in financial markets.

The RBNZ is engineering a sharp slowdown. They want inflation back to 2%, and at 5.6%, there is still a long way to go. The full force of the last two years of monetary policy tightening is still working its way through the economy. Monetary policy works with long lags. But most of the impact has hit households and businesses. Household budgets are being stretched. And businesses now worry more about demand for their product or service, as well as costs. On top of the rapid rise in interest rates, high rates of inflation have slashed household purchasing power, and falling house prices have dented confidence and the ‘wealth effect’. But it’s not all bad news…

The biggest development this year happened at the border. There has been a surge in migration. More foreign workers are coming and plugging the gaps in our tight labour force. They will reassert downward pressure on wage growth. At the same time, migrants boost demand for everything, including housing. The migration-induced boost to our team of 5mil, actually make that 5.3mil, has led us to revise up our projections for the Kiwi economy, but only just.

Ultimately, the surge in migration will add demand to a languishing housing market. Confidence is returning already, and the demand/supply imbalance will remain fundamental to the outlook.

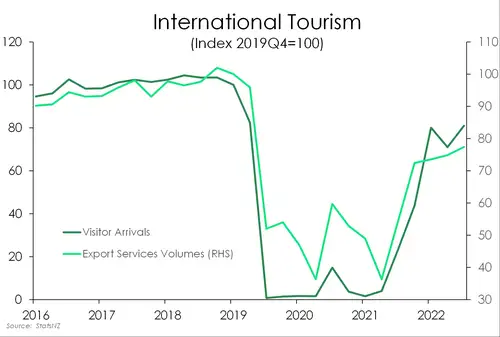

We’re watching out for a full return in tourist numbers. Aotearoa is, and will always be, an attractive place to come for work, study or play. A further bounce in tourist numbers will boost our service exports. And there’s plenty of upside. We’re still working our way back to pre-Covid levels. Tourism is at about 70% of pre-Covid levels… levels we will surpass.

Special topic on migration: More than just a Covid catch up

Come one, come all; they keep on coming. “Give me your (tired) strong, your (poor) rich, your huddled masses yearning to (breathe free) be a tradie”

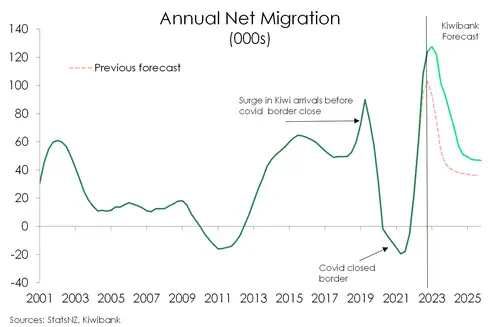

In our previous forecasting round, we expected net inflows to top out around 100k by September. But not only did we get there sooner (August), but migration continues to climb. In the year to October, arrivals exceeded departures by over 128k – another record high. To be fair, migration data while incredibly timely, is incredibly volatile and subject to big, big revisions. Recently, we’ve come to expect significant upward revisions. Our forecasts back in June were working off smaller numbers. So we return to the drawing board with a much stronger starting point.

Evidently, the strength in migration has not dissipated as quickly as we had expected. Once the borders were fully reopened, migrants whose plans to live the Kiwi dream were previously thwarted, came flooding back. We had thought the above-average, double-digit net inflow earlier this year was simply pent-up demand in play. But we’re nearing the end of 2023, and we are still recording above-average inflows.

In the October month alone, a net 7,819 landed on our shores following last month’s 10k net gain. It’s getting harder now to put down the surge to a ‘Covid catch-up’. Given the large influx throughout this year, it is going to take some time for the annual numbers to settle. We may even settle at a higher level than initially assumed. Because prior to Covid, migration was already running hot. The border restrictions disrupted the trend, forcing people to return to ‘home base’. And for us, that meant net migration running at a loss (outflow) for the first time since 2011. But that was just a (brief) moment in time. When we look back on this period, the Covid years (2020-23) may indeed be regarded as a historical anomaly. Because we expect net migration to resume its pre-Covid trend. And if anything, the net inflow may run at levels above pre-Covid given that immigration settings are relatively looser today than yesterday. We see migration slowly falling back from here, and settling at around ~45k in a few years’ time.

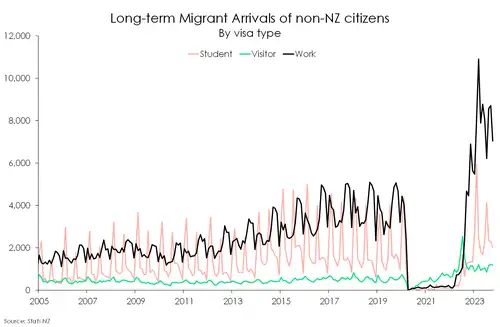

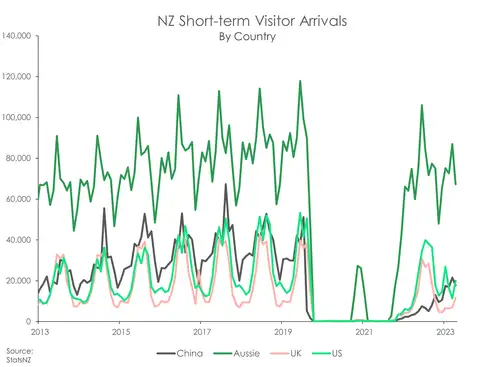

Strong inflows of non-NZ citizens continues to be the key driver of the current boom. In the year to October 2023, we recorded a (record high) net gain of 173,400 non-NZ citizens. And like pre-Covid trends, citizens from India have dominated inflows, followed by the Philippines and China. Considering that Covid restrictions in China were only lifted earlier this year, there’s upside potential to Chinese arrivals. Most arriving in Aotearoa are also of working age. In the last 12 months, over 40% of the net gain in migrants has been concentrated within the 20-34 year age bracket. And arrivals on work visas reached a record high annual total of over 92k. Similarly, arrivals on student visas exceeded 30k – another record high. And international students studying here typically move into the workforce (as most student visas allow up to 20 hours of work per week).

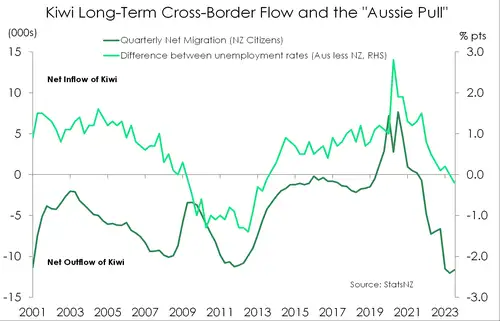

A risk that net migration settles below forecast is the uncertainty around the flow of Kiwi. We have returned to recording the typical net outflow. But there are even more Kiwi leaving home, than there are Kiwi returning. In the last year, over 26k Kiwi returned to the burrow, but that was more than offset by over 70k outgoing Kiwi. When it comes to migration flows, the pull of work is a powerful one. And the labour market across the Tasman is expected to be quite the magnetic force. The Kiwi economy will likely struggle to weather the storm of high interest rates. Because we are facing into worse conditions, given over 500bps of rate increases from the RBNZ. By comparison, the RBA opted for a lighter touch in battling inflation – just 425bps of hikes and delivered in a staggered fashion. It may be relatively smooth sailing for the Aussies. As a result, our unemployment rate may rise faster than that of our Antipodean counterpart. A measurable outflow of Kiwi – bigger than pre-Covid levels – is likely to persist for the foreseeable future.

The two faces of migration

The impact of surging migration is two-sided. On the helpful side, the influx of youthful migrant workers is expanding the labour force and dampening wage pressure. The disinflationary force is especially strong given the tightness in the labour market to begin with. Employers were starved of workers. And our surging migration is helping to satisfy appetites, quickly. The labour market is softening, at a time when the demand for workers is starting to ease. Businesses are more cautious than they were a year ago. But on the other side, more people mean more demand. And signs of an increase in demand are surfacing.

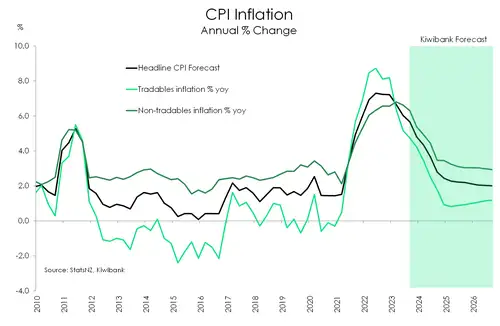

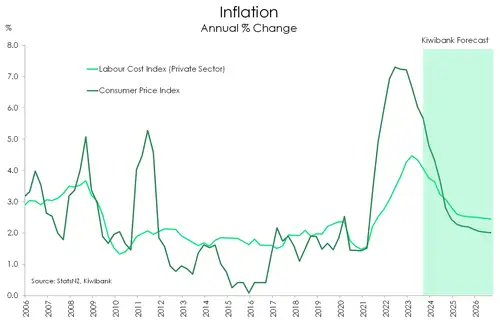

For this reason, we’ve lifted our inflation outlook. Inflation has been above the RBNZ’s 1-3% target band since mid-2021. And it’s going to take some time to get back to the 2% midpoint. We’ve seen headline inflation fall from the 7.3% peak to 5.6%. And we expect it to hit ~4.8% by year end 2023. For inflation to fall from the 7s into the 6s, 5s and now the 4s – that’s quite the psychological shift.

But rapidly decelerating imported inflation is doing most of the leg work. Favourable base effects are still in play with last year’s spike in energy and food prices falling out of annual calculations. Cooling commodity prices are also helping to lower the cost of imports.

The tricky part is getting back to the 2% target midpoint. And it all hinges on domestic inflation – the stickier, demand-driven kind. And with surging migration, the risks are tilted to the upside. Rents in particular are high above pre-Covid levels, and rising. Broader pressure within the housing market will also mean stronger house price growth. And with that, comes the wealth effect. Consumption is weak at present, but would be even weaker if not for a fast-growing population. However, we still forecast the return to 2%, albeit delayed, as the economy continues to cool and the labour market loosens further. We see inflation back within the band by the second half of 2024. That’s about a quarter longer than we had previously forecast. It’s not until 2025 that we see inflation settling at 2%.

Rising migration has also prompted an upgrade to our economic outlook, once again. We have shaved off a few %pts from our previous estimate. We now expect the economy to shrink over the Dec-23 and Mar-24 quarters, totalling a 0.2% contraction (we previously had a contraction of 0.4%). By the simplest of definitions, it is a ‘recession’ and one of even shorter duration and shallower magnitude. But whether or not output runs backwards, make no mistake – the economy is weakening under the weight of the RBNZ’s heavy hand. If we include periods of (effectively) no growth in 2024, then we expect about 12-straight months of soft activity. And given a fast-growing population, it’ll surely ‘feel like’ a recession for the average Joe or Jane on the street. Their slice of the economic pie may well be shrinking.

Tourism remains an upside risk to bear in mind. Despite a solid bounce back from the pandemic, tourism is still not yet where it once was. Current levels in October show tourism sitting at about 80% of pre-Covid levels. At first the full return to pre-Covid levels was hindered by a mix of capacity constraints and waning demand. Now the return of migrants has helped plug employment shortages in the industry and it’s all about weak demand. Though not from everywhere. For the most part, short-term visitor arrivals from Australia, the United States and the UK have returned to pre-Covid levels. But it’s our Chinese tourists, our second largest market after Australia, that are falling short of the mark. Chinese visitor arrival numbers are still down around 70% of pre-Covid (2019) levels. And our tourism sector needs a rebound in Chinese arrivals to get back to full strength. Economic weakness in China is hindering travel demand. But the upside risk remains. A return to full strength tourism could very well see us avoiding our forecasted shallow recession.

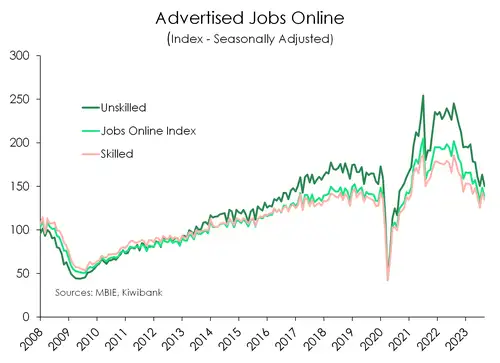

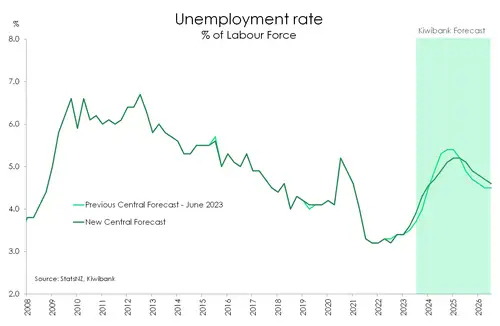

Tightness in the labour market is quickly abating. The unemployment rate has moved away from record lows and closer to pre-Covid levels. For now, a migration-induced boost to labour supply is driving a loosening in labour market conditions. But the narrative is beginning to shift. Demand for labour is softening. Firms are no longer hiring with the same gusto. And neither are firms searching for workers with the same desperation. The forecast economic slowdown should also see slack emerge. As consumer demand cools, so too will firms’ demand for labour. If firms are expecting to pump out less output, then an extra pair of hands may prove unnecessary, and indeed too costly.

There’s been a mindset shift among businesses, and employment intentions are weakening. There’s a strong correlation between employment intentions and actual employment growth. It’s only a matter of time before those weaker intentions translate into weaker growth. We are expecting the unemployment rate to continue rising to a peak of 5.3% early in 2025. That’s slightly below our previous forecast, given a stronger economic outlook. However, unemployment is expected to remain elevated for longer. Greater slack in the market however is a must in order to cool down domestic inflation. Wages are often the largest input cost for businesses. And a tight market has seen wage inflation spike, which in turn lit a fire under services inflation. But as capacity in the market builds, wage growth should moderate and flow through to a cooling of domestic price pressures. We see wage growth continuing to decelerate, but at a slower rate than consumer price inflation. We see wage growth outpacing inflation, for the first time since pre-Covid by the second half of 2024. It should be a slow end to the cost of living crisis.

Fortunately, the tight labour market has helped cushion the blow of the housing market downturn. And the surge in migration has led to an earlier-than-expected end to the correction. House prices have fallen back to early-2021 levels, recording a 17% peak (Nov-21)-to-trough (May-23) decline. And there are tentative signs of recovery. Sales activity is picking up, and the number of “days to sell” is reducing. We expect house prices to continue recording gains, but of a relatively modest amount (~6%). The migration boom and the new government’s promise of a reversal to a few property rules (interest deductibility, Brightline test, CCCFA) are significant tailwinds to consider. But the market continues to face the steepest interest rates in 15 years – with risk of lifting further – and a forecast rise in unemployment. Such headwinds will likely cap any house price gains in 2024 (see Special Topic on Housing below).

The influential global outlook

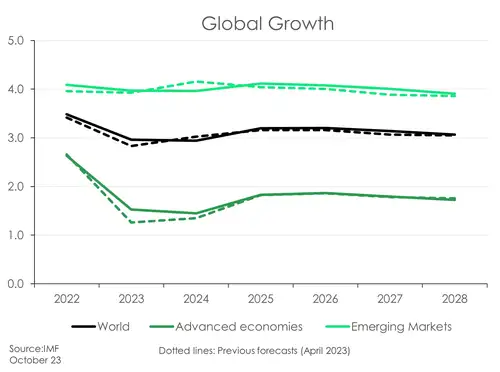

As always, no analysis is complete without looking at the global picture. After all, we’re a small open economy with large exporting industries. A global slowdown, on top of a slowing domestic economy, is going to hurt. Subdued growth is needed to continue taming global inflation.

Global growth is forecast to remain below trend of 3.8%. In 2022 global growth was already at 3.5%, and is expected to come in around 3% for 2023. In 2024, the IMF forecast growth of just 2.9%. And that’s another downward revision. Over the medium term, global growth is set to remain at its lowest level in decades. It’s not pretty. But it’s what’s needed to bring inflation back towards target. Global inflation reached a peak of 10.3% in 2022. That’s since moderated with aggressive monetary policy tightening across most major central banks.

For some, like the US, it’s looking more and more likely that a soft landing may be possible. US inflation has fallen to 3.1%. But still, inflation remains at large. Currently 5.5%, the IMF sees global inflation holding around these levels over 2024. The IMF’s inflation guesstimates are stronger than previous estimates as several economies, including ourselves, have proven more resilient. Supported by strong labour markets, inflation has proven very sticky. As such, keeping rates “higher for longer” has become the mantra for many central banks.

The balance of risks abroad remains tilted to the downside. Our largest trading partner, China, is also our largest vulnerability. Since re-opening from Covid restrictions earlier this year, China has continued to experience faltering growth. Despite policy easing, China’s property and debt crisis has spread its way through to lower investment, high rates of youth unemployment, lower consumption, and even deflation. As such, growth forecasts for China continue to be revised lower, concerning commodity exporters like us. China’s weakness undoubtedly has spill over effects for our trading partner growth. Already, we have seen sharp declines across our commodity prices with waning demand. With around 20% of our growth revolving around exports, there’s potential for huge downside risks.

Special topic on Kiwi housing: The great summer BBQ debate

- Everything that is wrong with our housing market is due to a lack of supply. But policymakers focus on demand. We need better infrastructure, more plots, more houses. And affordability will follow.

- It has been a wild ride for Kiwi property. Surging migration, again and again, record low mortgage rates, and then the reversal, have seen property prices fluctuate wildly. What’s next?

- Well, house prices are more likely to rise than fall, for the right and wrong reasons. Our housing shortage is getting worse. Activity is improving. And prices are stabilising. It’s Déjà Vu. Migration surges, prices rise.

- Interest rates will play a big role. Rates may rise a little more. And then they may fall, later next year.

Most policymakers focus on demand. It’s the side they can influence. More must be done to increase the supply of land (and all the utilities and services required) for development if we are to respond to surges in population.

At a time when we need the supply of homes to surge, to meet migration demand, we’re seeing a fall in consents. Over the last year or so, the decline in housing activity and prices have seen builders scale back. It’s expensive to build in NZ, for a variety of unacceptable reasons. And developers are no longer getting the premium price they need. Pre-sales are also soft.

What to expect in 2024 and beyond

Forecasting is as much an art as it is a science. But the data has turned north, and we can feel the lift in confidence amongst mortgage brokers, real estate agents, investors and customers. We think we’re much more likely to see price gains, rather than falls, over 2024.

The surge in migration will play a big role. The demand/supply imbalance will worsen. The surge in migration and the loss of dwellings at high risk of climate change will only exacerbate the housing shortage. The new Government will play a big role. Because the ‘promised’ reintroduction of interest deductibility, shortening the Brightline test timeline, and possible watering down of the CCCFA, will entice investors. Any added infrastructure spend or incentives for new builds will also be welcomed. Interest rates will also play a large role, eventually. We think rates will fall in 2024. But buyer beware: The RBNZ is threatening to hike again. So there may be a lift near-term.

Our best guess is house prices will rise by 5-to-7% next year. Call it 6% to sound precise.

Interest rates will bounce around, and hopefully fall

The outlook for interest rates is interesting. It looks like a game of two halves. Right here, right now, interest rate markets are pricing in perfection. The ‘soft landing nirvana’, that many central banks and analysts are forecasting, involves a swift return of inflation back to 2%, very modest growth without harsh recessions, and a fair and reasonable loosening in labour markets.

Calling it (too) early, market traders are positioning for a quick and easy loosening in financial conditions. Rate cuts are being priced in the first half of 2024. The near perfect outcome is not without risks, either way.

This is what (near) perfection looks like. We have no hikes priced. That’s beautiful in itself. But it’s beauty the RBNZ does not yet endorse. And then we have the first full cut priced in August (5.24% priced) next year, followed by another in November (5.0% priced), two cuts by May 2025 (4.53% priced) and a shallow easing towards 4.25% into 2026. It’s easy to argue either side of this trajectory.

We have sympathy for the view that the RBNZ could start cutting from August next year. We recently adjusted our call for cuts to start in May, to November. We did so after the RBNZ delivered a threateningly hawkish diatribe in November’s MPS. So near-term, rates markets could back up, and see more chance of a hike and less chance of cuts. But ultimately, we believe the next big move is down.

It's a game of two halves. Interest rates will remain elevated (and even rise further) in the first half. And then a big swing lower in the second. If rate cuts come as early as November next year, our prediction, then the move could be more abrasive. We’d expect the RBNZ to move swiftly back towards a neutral setting. Neutral is currently estimated to be around 2.5%. The market currently has a move to 4.25%. That’s too high if the RBNZ are moving back to neutral. The second half of the year could see an even more pronounced shift lower in interest rates (globally).

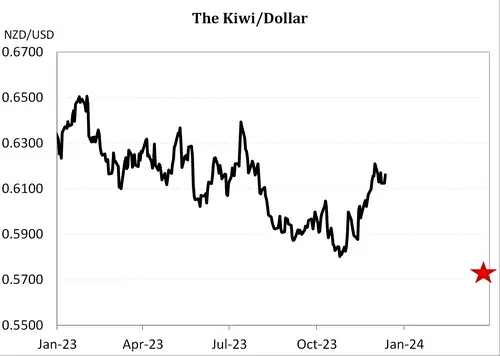

The Kiwi has regained flight, but still faces headwinds

The Kiwi dollar has outperformed our expectations this year. We had forecast a decline to 55c. Instead, the recorded low in the Kiwi was a short-lived 57.70c. We came close, but not close enough. The Kiwi was in a downdraft for much of the year, as expected, but bounced in November. It was the RBNZ’s stern message that gave the Kiwi wings.

Growing speculation of Fed cuts early next year, ahead of the RBNZ, also fuelled the rally. Now the Kiwi is flying high at over 61c. It’s down from the 63-to-65c range at the start of 2023. But it’s higher than we thought. We think the Kiwi will remain elevated into 2024, as the RBNZ’s hawk-like feathers fly higher and shine brighter than their central banking peers. Ultimately, we think the cooling in global demand and reduction in inflation pressures will weigh on the bird. But that may take many a month to see. For the same reasons we forecast a decline to 55c this year, we forecast a decline to 57c next year. It will be a volatile downward glidepath. It always is. But we expect the Kiwi to ultimately fall into a 55c-to-59c range. Basically, we expect to re-record the recent lows.

All content is general commentary, research and information only and isn’t financial or investment advice. This information doesn’t take into account your objectives, financial situation or needs, and its contents shouldn’t be relied on or used as a basis for entering into any products described in it. The views expressed are those of the authors and are based on information reasonably believed but not warranted to be or remain correct. Any views or information, while given in good faith, aren’t necessarily the views of Kiwibank Limited and are given with an express disclaimer of responsibility. Except where contrary to law, Kiwibank and its related entities aren’t liable for the information and no right of action shall arise or can be taken against any of the authors, Kiwibank Limited or its employees either directly or indirectly as a result of any views expressed from this information.