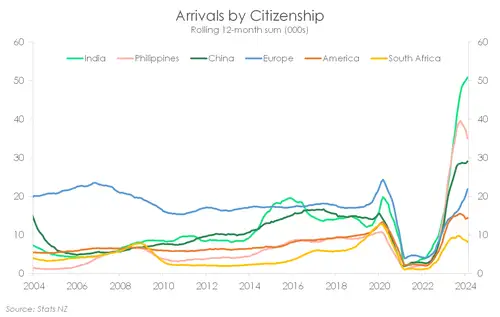

Most migrants have arrived from India, the Philippines and China. And it’s in our largest cities that they establish their new lives. It’s no surprise that these regions have also recorded the largest increases in employment and consumption.

At the outset, the current migration boom has been more disinflationary. Strong migration is helping to cool the labour market. The demand effects, with rising rents, however, are beginning to emerge.

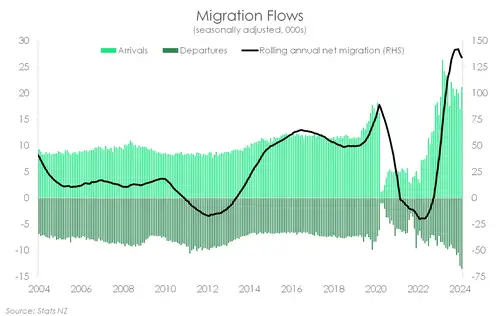

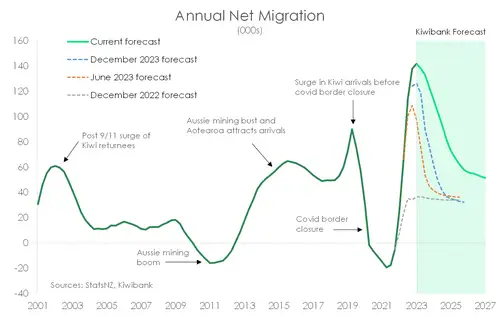

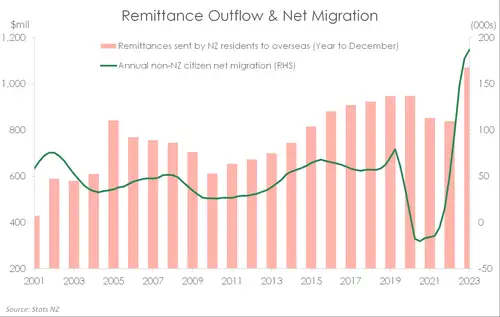

2023 was the year of a record-breaking, head-scratching, heart-palpitating surge in migration. At its peak, arrivals exceeded departures by a mammoth 142,000. In our previous forecasting round, we guessed around 130,000. But once again, historical revisions were large. Migration data is timely, but incredibly volatile with big revisions. Our above-consensus forecast, just four months ago, worked off smaller numbers. We return to the drawing board with a much stronger, and upwardly revised, starting point.

Inbound migration has not dissipated as expected. We always knew people would come flooding back to Aotearoa once the border reopened. NZ Inc. performed remarkably well throughout the Covid pandemic. Our little corner of the globe was viewed as an oasis. But we have been surprised by the strength in migrant inflows, well into 2024. Long-term arrivals appear to be stabilising, but at above-average levels. While the number of departures has increased, the number of arrivals more than offsets. And given the influx throughout 2023, it’s going to take some time to get back to the pre-Covid average.

Prior to Covid, the 2014-2019 period recorded the largest migration boom in recent history. Border closures during Covid interrupted this. Net migration (briefly) turned into an outflow, before a remarkably rapid recovery. Our previous forecasts expected migration to settle at around 32k, below the pre-Covid average. We initially judged the recovery as pent-up demand that would eventually wane, and relatively quickly. But the data continues to be revised higher. It’s no longer a simple Covid catch up. Rather, it’s more of a continuation of the migration boom that began in 2014. And we have upgraded our forecasts. Looking ahead, we expect net migration to return to its pre-Covid average of around 40-50k.

A key uncertainty surrounding our forecast is the Government’s recent changes to immigration settings. The criteria for entry have been tightened and may result in a faster-than-expected decline in arrival numbers. We may see net migration settle below our forecast, as a result.

There’s a demand and supply force to migration. In the current boom, the supply-side influence has been the dominant force. High inflows have boosted the productive capacity of the economy. The influx of migrants is helping to cool wage pressures. And the disinflation is especially strong given the tightness in the market to begin with.

On the demand side, consumption has been soft despite rapid population growth. Because migrants are arriving in a recession. The return of migrants has also coincided with a sharp lift in remittance outflows. Migrants are sending a portion of their wages ‘home’, spending less here.

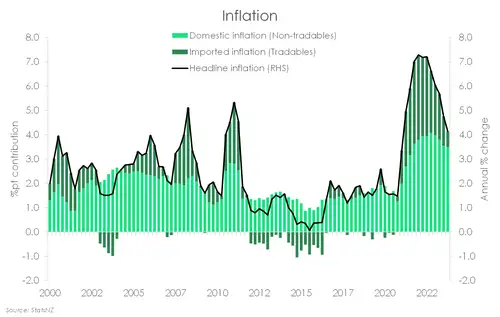

The current migration boom has simply generated less inflationary pressure than expected. That said, rental inflation has surged to an all-time high which frustrates the inflation outlook. Taming domestic inflation is key in ensuring overall inflation returns to the RBNZ’s 1-3% target band.

Where have they come from…

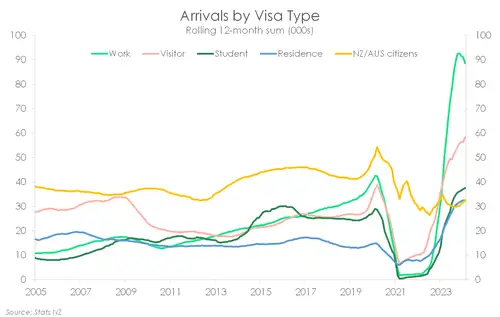

Since the middle of 2022, long-term arrivals have been on a steep climb. And over the first half of 2023, monthly inflows averaged 22,000 – more than double the long-term average. Arrivals began stabilising in the second half of 2023, albeit at elevated levels.

It has been almost two years since the border was fully reopened. Long-term arrival numbers began stabilising at the second half of 2023, but at elevated levels. On a monthly basis, we are still recording above-average inflows of around 20,000. The remainder of 2024, however, should be another story as firmer brakes have been applied. Recent changes to immigration settings have effectively raised the entry into Aotearoa. We’ll likely see a more meaningful slowdown in inflows in the coming months.

Like pre-Covid trends, most long-term arrivals have arrived from India. In the year to February 2024, 50,800 arrived from India. China was once the largest source of migrants. However, the 29,000 Chinese arrivals in 2023 falls short of the 35,000 arrivals from the Philippines. China still faced highly restrictive Covid rules for much of 2022/23 which held back inflows into NZ. However, the share of monthly inflows arriving from China is growing. In February, Chinese arrivals made up 17% of the total, up from 11% in the month prior. They’re making up for lost time.

…Where have they gone?

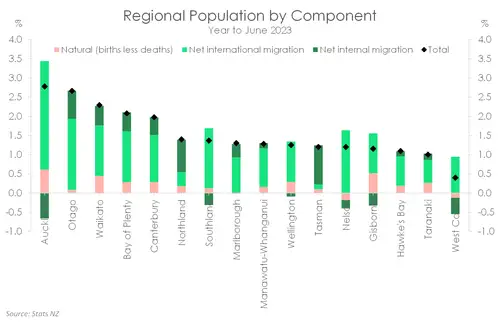

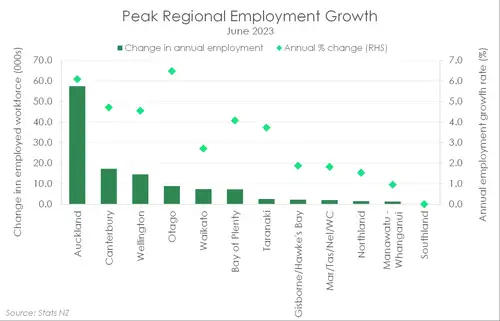

It's no surprise that Auckland has been the biggest beneficiary of the migration boom. Auckland’s population grew 2.8% in the year to June 2023, partly due to a net 47,800 increase in net international migrants. Wellington grew 1.3%, welcoming an additional (net) 5,700 international migrants.

Somewhat surprisingly, Otago’s population grew the most after Auckland. In the year to June, the region’s population expanded 2.7% largely due to a net international migration gain of 6,400. Today’s mix of migrants are concentrated within the services trade (see below). And Otago, specifically tourist-mecca Queenstown, is an attractive destination for migrants.

Young Kiwi take flight

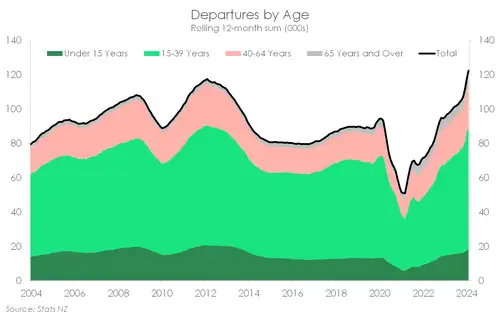

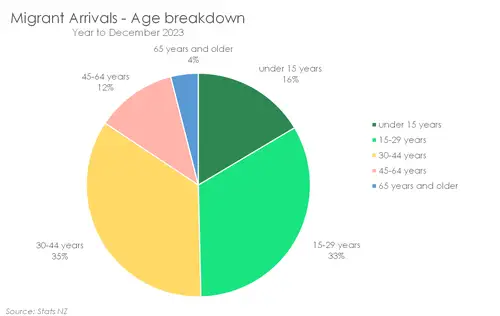

On the other side of the ledger, departures are climbing. In 2021, departures slowed to a record low of 50,970. But that’s now more than reversed with annual departures in excess of 100,000. Young Kiwi leading the exodus. We’re importing a young cohort, but we’re also losing a young cohort. The exodus was in part due to the pent-up desire to see the world. Over 27,000 Kiwi returned home in the year to February, but that was more than offset by the almost 75,000 Kiwi leaving the burrow. And of the 75,000 outflow, around 40% were aged between 15-39 years.

Kiwi account for more than 60% of migrant departures. As is typical, we recorded a net loss to the sharp tune of near 50,000. That’s the deepest annual loss on record. And one which continues to deepen. However, against the backdrop of a rapid rise in non-NZ net migration, the 47k (net) outbound Kiwi makes a slightly smaller proportion of our team of 5.3million.

At a turning point

We are now at a turning point. With each update, it is becoming increasingly clear that the surge in migration peaked last October (although the magnitude of which continues to be revised higher). The persistent strength in inflows however means the decline in net migration will unlikely be as swift as the rise. We previously expected the annual balance to settle around 30,000. Initially, we put down the 2023 migration surge as a Covid catch up. But the strength in the data has thrown that theory out the window. Instead, the numbers are playing out as a resumption of the 2014-2019 migration boom; the boom interrupted by the unprecedented border closure in 2020. We have upgraded our forecasts, and now expect a gradual decline to 40-50k over the medium term.

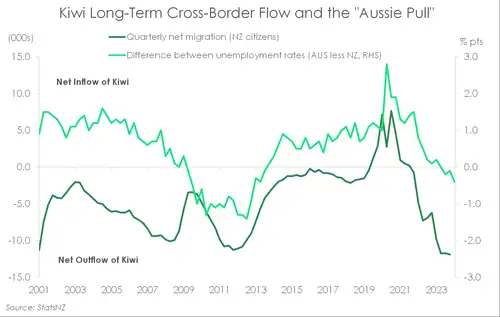

A key influence of our forecast is the relative strength of NZ’s labour market compared to major emigration destinations – like Australia and the UK. The pull of work is a powerful one when it comes to migration flows. The chart below shows a stronger Australian labour market, compared to NZ.

At the same time, we have witnessed a return to net outflows of Kiwi offshore. We expect the Aussie labour market to retain its relative strength. The RBNZ has been more aggressive than the RBA in slowing the economy. The RBA raised rates by 400bp, far fewer than the RBNZ’s 525bp. The RBNZ also had a seven-month head start. As a result, the Kiwi economy is cooling much faster, with output contracting four out of the five previous quarters. The Kiwi unemployment rate will likely rise faster than that of our Antipodean counterpart. It’s already begun. The Kiwi unemployment rate has risen over 1% to 4.3%, on its way to above 5% by year-end. By comparison, the Aussie unemployment rate has been stuck at 3.9% since last November. Tighter offshore markets, like across the Tasman, mean a measurable outflow of Kiwi – larger than pre-Covid levels – will likely persist.

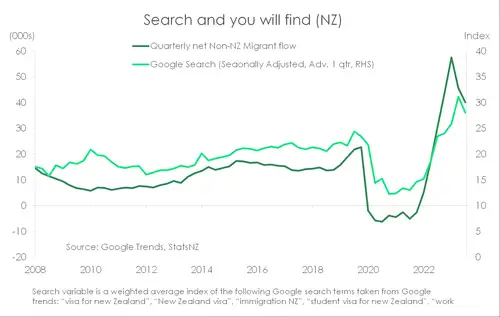

Our migration forecast also hinges on the trajectory of non-NZ net migration. Annual non-NZ net migration reached 186,900 in February. Google trends warned of such an influx. Worldwide searches on Google for “NZ visa” and related terms skyrocketed once the border was reopened. We recognise that an online search is a long way from actually packing up and moving overseas. Some of these search terms simply reflect the desire to travel, not necessarily the willingness to live in NZ. And for some countries, such as China, they are underrepresented in the data. In China, homegrown search engines are more widely used than Google.

Nevertheless, the data (rightly) signalled a sizable desire to move to our corner of the world. However, the data is now telling a different story. Google searches appear to have peaked in 2023. Around the same time, quarterly net non-NZ inflows also pivoted lower. We expect the slowdown to continue, with net non-NZ inflows easing to ~20K on a quarterly basis over the medium-term.

A key risk to our forecast is the Government’s recent changes to immigration setting. With much more restrictive settings, arrivals may decline much faster than we expect. At the same time, NZ is still competing with other developed countries for skilled migrants. The net result of the forces means annual net migration may settle below our forecast. We’ll be keeping watch.

A double-edged sword

Strong migration adds to both demand and supply. Adding demand tends to be inflationary, while adding supply is deflationary. Previous booms, particularly in the early 2000s, caused a much more significant increase in the demand for goods and services.

In the current boom, the supply side influence has been the dominating force, so far. However, the demand effects are beginning to emerge. But what’s the net impact? First, let’s examine the evidence on both side of the migration coin:

Supply: More twiddling thumbs

The immediate impact of migration has been the boost to the productive capacity of the economy. Staff shortages was a cry heard across industries during Covid. From IT to retail and agriculture to construction, all were screaming out for workers. In 2022, the border was fully reopened, and the talent pool greatly expanded. In NZIER’s latest business survey, firms reported that it is now easier to find both skilled and unskilled labour. Labour as a constraint on output has declined since the start of 2023, after being the factor most limiting output throughout 2022.

Migrants arrive at a working age, and they’re keen to work. Indeed, around a third of arrivals are aged between 15-29 years. Arrivals on work visas also reached a record high of near 100,000 in 2023. Similarly, arrivals on student visa exceeded 35,00 – another record high. Once again, that’s an increase to labour supply. Because international students typically move into the workforce, as most student visas allow up to 20 hours of work per week.

In the early stages of the migration boom, employment surged alongside it. Annual employment growth reached a high of 4.3% in June 2023. Unsurprisingly, the regions recording the largest net international migration also experienced the largest jobs growth. In terms of levels, Auckland’s workforce grew the most, up 57,400. In Wellington and Canterbury, the number of people both jumped by around 20,000. Comparing to a year ago, Otago recorded the biggest increase with a 6.5% jump in employment. It follows the concentration of new migrants among service-related occupations.

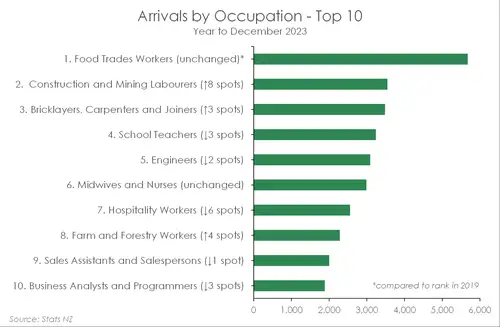

Compared to pre-covid (2019), the composition of the top 10 occupations has shifted – more service-related occupations and fewer professionals. Over 2023, food trades workers – think chefs, cooks and butchers – remained at pole position But construction and mining labourers climbed 8 spots to claim second place. Not far behind, were bricklayers and carpenters in third place (up 3 spots). Farm and forestry workers also made it into the top 10, climbing from 12th place in 2019. Engineering professionals however have fallen down the rank, as have business analysts and programmers. The shift in supply reflects the shift in demand. Staff-shortages were broad-based, but particularly acute in hospitality and trades. This is now reversing.

2023 was the last hurrah for the Kiwi labour market; a time when unemployment was still near record lows. It’s now 2024, and labour market conditions are beginning to ease. Labour demand is no longer as strong as it once was, and employment growth is slowing. However, we are still adding to the working age population. With fewer employment opportunities, but more hands available, unemployment remains on an upward trajectory. Consistent with a loosening in market conditions, wage inflation is also easing. To this extent, high net migration has been disinflationary.

On the demand side, the impact of high net migration has been less clear. Some sectors that would typically benefit from a growing population have underperformed. But where the demand effect is becoming more apparent is in rents. And that’s generating unhelpful inflationary pressure.

Demand: Retail down, rents up

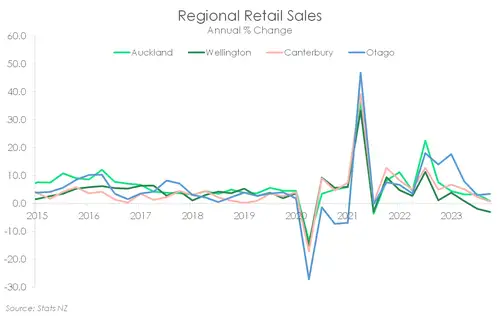

Despite rapid population growth, retail trade has been surprisingly soft. At the national level, retail trade declined 0.3%yoy last December. Bright spots are few and far between. And where they shine are in the regions experiencing the largest migrant-led increases in population. But it’s a dim light. In every region, retail trade has been trending down since late 2022. So much for the City of ‘Sales’, Auckland retail sales grew just 0.9% in 2023 compared to a year ago. And in Wellington, sales declined 3%. After adjusting for inflation, the contraction in per capita sales, down 6.7%, reveal an even bleaker truth. It’s looking like a repeat of the ’08 crisis. Households are clearly spending less as high interest rates and rising prices weigh on wallets.

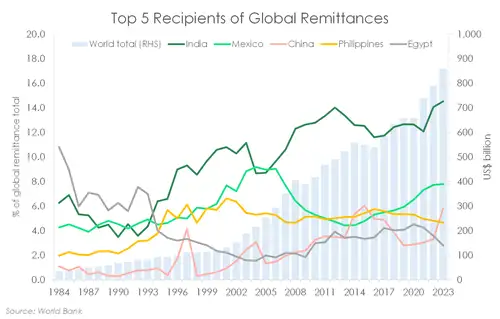

The recovery in remittance outflow may also explain why consumption has not been as strong as rapid population growth might suggest. According to the World Bank, global remittances received declined 0.8% in 2020 as Covid reduced immigration rates. NZ contributed to the slowdown. The amount of remittances sent by NZ residents to overseas dropped 10% below pre-Covid levels in 2021, but sharply recovered in 2023. Annual remittance outflows exceeded $1bn for the first time in 2023. Undoubtedly, inflation is working behind the scenes.

But the all-time high coincides with the 2023 migration boom, specifically the strong inflows from India. India has long-been the top recipient of global remittances. According to the World Bank, India accounted for 14.5% of global remittances in 2023. China and the Philippines are also among the top five. And it is migrants from these countries that make up the bulk of arrivals into Aotearoa. But as migrants send some portion of their wages back to their home countries, it suggests weaker local consumption than otherwise. The absence of a migration-led boost to consumptionpoints to a weaker inflation impulse than one might have expected from a fast-growing population.

In saying that, where migration is generating inflationary pressure is in rents. Rental inflation has surged to an all-time high of 4.7%. Once again, the regions facing the largest rent hikes are those recording the fastest population growth. In Auckland, rental inflation hit a high of 8.2% last September, while Wellington rents jumped 3.9%.

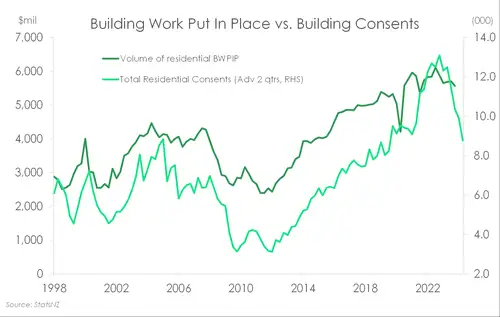

It certainly does not help that residential building activity has slowed down. New dwelling consents peaked at the height of the housing market boom in November 2021. Since then, activity has been on a downtrend. Building activity is simply not keeping pace with population growth. And as Economics 101 teaches, prices rise when demand outstrips supply. The ongoing strength in rents is a key reason why domestic inflation is barely budging lower.

The verdict

At the outset, the current migration boom has been more disinflationary. Strong migration is helping to cool the inflationary pressures stemming from the labour market. And the disinflationary force is especially strong given the tightness in the labour market to begin with. The expansion to the talent pool has brought an end to the salary war of 2022.

Wage inflation has eased, and we forecast the cooldown to continue this year. That’s important for the inflation outlook. Inflation has fallen steeply from the 7.3% peak, led by a rapid deceleration in imported inflation. Now, inflation is largely being driven by domestic price pressures, specifically services where labour makes up a large share of costs. Taming wage growth is key to bring overall inflation back to the RBNZ’s 1-3% target band.

Some aspects of migration’s boost to demand have also been less inflationary than expected. Migrants have arrived at a time when inflation is high and interest rates are restrictive. Tight financial conditions and the jump in remittance outflows have resulted in weaker local consumption than the rapid population growth might suggest. That mitigates the inflationary potential of the surge in migration.

That said, where we are most concerned is the upward pressure that a growing population is putting on rents. Rents make up 10% of the consumer price index, and is supporting persistent domestic price pressures. Our infrastructure, specifically housing, has been unable to accommodate a growing diaspora.

Long-term, net migration is generally a net positive for the economy. Immigration-fuelled diversity can boost economic prosperity and create a culturally rich society. But without addressing our deep infrastructure deficit, migration will likely exert more inflationary pressure than is necessary.

All content is general commentary, research and information only and isn’t financial or investment advice. This information doesn’t take into account your objectives, financial situation or needs, and its contents shouldn’t be relied on or used as a basis for entering into any products described in it. The views expressed are those of the authors and are based on information reasonably believed but not warranted to be or remain correct. Any views or information, while given in good faith, aren’t necessarily the views of Kiwibank Limited and are given with an express disclaimer of responsibility. Except where contrary to law, Kiwibank and its related entities aren’t liable for the information and no right of action shall arise or can be taken against any of the authors, Kiwibank Limited or its employees either directly or indirectly as a result of any views expressed from this information.