We believe inflation is peaking, around 7.1%, and will ease into 2023. Global inflation pressures, while persistent, will eventually abate. Similarly, domestically generated inflation is also likely to moderate into 2023. The speed at which inflation eases will determine the peak in interest rates.

Ultimately, we expect the RBNZ’s actions over 2022 to have a magnified impact on growth into 2023. We suspect the RBNZ will underdeliver on said interest rate hikes. House price falls and the negative wealth effect will ultimately limit the amount of rate hikes. We expect the cash rate to peak at 3.5%, not 4%.

Interest rate cuts may be a consideration into 2024…

We have updated our economic outlook. We find ourselves in a world with more persistent inflation and a more determined central bank. Consequently, we have much higher interest rates and a weaker housing market. Kiwi households face a cost-of-living crisis and much higher mortgage rates. Consumption growth will stagnate. Kiwi corporates face a plethora of challenges, including a very tight labour market and rising wages, margin pressure, and continued difficulty in sourcing product (with disrupted supply chains). Confidence in the economy has been hit, and investment intentions are contracting.

The RBNZ is hell-bent on returning inflation to the target band of 1-3%yoy. The lift in inflation expectations is challenging the central bank’s credibility. And the central bank is hiking at double-speed (50bps moves). A cash rate of 3.5% is expected by November, up from 2% today. And the RBNZ is forecasting a continued push to 4% in 2023. This is the fastest tightening cycle in decades. Mortgage rates have doubled in the last year. And they have further to rise.

Under the weight of regulatory changes, macroprudential policy shifts, and rapidly rising interest rates, the housing market is in retreat. The negative wealth effect from falling house prices will suffocate household consumption and ultimately limit the amount of RBNZ tightening needed.

Looking offshore, the global economy is cooling. Inflation is running at 8% globally, and central banks are following the RBNZ in their eagerness to tame the inflation beast. Global interest rates are rising. And global growth rates are waning. The combination of a war in Ukraine and Chinese lockdowns have seen commodity prices soar, and supply-chain fragility once again exposed. The risk of a recession in many of Aotearoa’s key trading partners has risen. Global growth forecasts have been slashed in recent months. Of course, this feeds into the Kiwi economic outlook as well.

We’ve downgraded our Kiwi economy’s forecast. We see demand easing over the next few years.

Global headwinds gather

Recession fears are building offshore. The war in Ukraine, concerns about the Chinese economy and aggressive tightening from central banks have all raised the prospect of a global downturn. And some alarm bells are already ringing. Copper, which is often perceived as a barometer of global economic growth, has tumbled over 10% from its record high set in March.

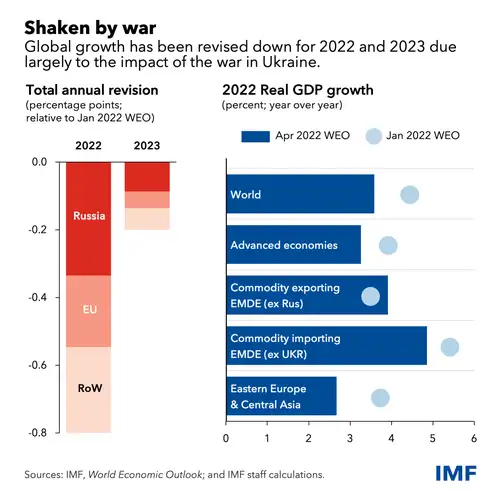

In the IMF’s latest (April) outlook update, it materially downgraded its growth forecasts. Global growth is projected to slow significantly from 6.1% in 2021 to 3.6% in 2022 – down from January’s 4.4% forecast. The downgrade is largely a consequence of the war in Ukraine.

Though the war may be confined to Ukraine, the economic damage will spread far and wide through commodity markets and trade linkages. Indeed, the weaker outlook for the European Union (2.8% in 2022, down 1.1%pts) is a leading culprit for the weaker global economy outlook.

The lockdowns in China also adds to the wall of woes. China’s strict covid measures – including locking down key manufacturing and trade hubs – will stunt activity and exacerbate supply chain bottlenecks. Already, the zero-tolerance covid strategy has seen industrial output contract (-2.9%yoy in April) for the first time since March 2020.

The inflation outlook too has deteriorated. Commodity prices have spiked, especially for food and fuel, due to the war and sanctions on Russia. And price pressures are broadening given acute supply and demand imbalances. The IMF expect inflation to be more persistent than projected in January. Projections for 2022 were raised to 5.7% (+1.8%pts) in advanced economies and 8.7% (+2.8%pts) in emerging economies. It’s higher for longer.

But that’s not what central banks want to hear. The spike to decades-high inflation has prompted a 180° pivot in monetary policy. Interest rates are firmly on an upward trajectory as central banks act to quell rapidly rising inflation. Many have even signalled their intent to take rates through neutral into true tightening territory. Rising rates are needed for demand to moderate. But the ‘fast and furious’ approach casts doubt on whether central banks can indeed achieve a ‘soft landing’ for the economy. And unfortunately, history is not on their side.

Overall, the outlook has darkened, and the risks are skewed to the downside. The emergence of new covid variants would prolong the pandemic, and induce renewed economic disruptions. An escalation of the war in Ukraine cannot be ruled out. And the further inflation expectations float away from targets, risks (even) more forceful action from central banks. More aggressive tightening however would risk killing rather than cooling demand, pushing economies uncomfortably closer to the edge.

Demand and supply must rebalance…

On top of the inflationary pressure from offshore, the Kiwi economy has too much demand relative to its ability to meet it. Labour and material shortages are evident, particularly in the construction sector, and supply-chain snarl-ups continue to delay deliveries.

So, the RBNZ is yanking on the hand brake by lifting interest rates aggressively (see our markets section below). The RB must. Keeping inflation low and stable is mandated. And demand needs to be cooled to push inflation down back to target. Such aggressive tightening has its consequences. As such, we have downgraded the outlook for the economy and see demand easing over the next few years.

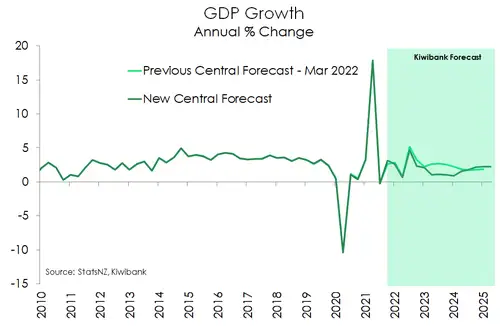

Despite omicron sinking its teeth in over the March quarter, GDP growth looks to be robust thus far. It’s the second half of this year onwards that looks shakier. High inflation and rising interest rates is eroding firms’ profitability and straining households’ budgets. Consumer and business confidence is in the doldrums, and forward indicators of activity have fallen once again. We’re not forecasting a recession, but we acknowledge the risks of one are rising.

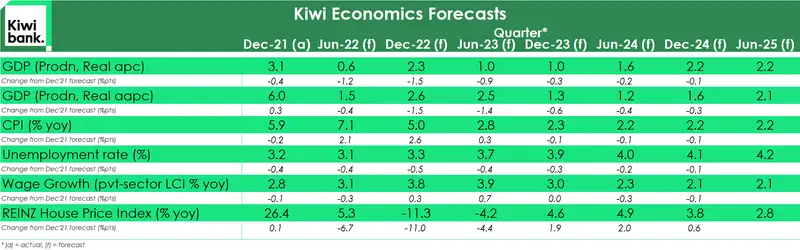

Following last year’s covid disrupted recovery, we expect GDP growth to halve for 2022 from ~6% last year to a more ordinarily 3%. However, tightening monetary policy – and less stimulatory fiscal policy – at home and a weakening global economy is expected to see growth halve again in 2023 to just 1.4%. The outlook for 2023 and 2024 have been revised down notably since our last set of forecasts (see chart above).

…because inflation is far too high

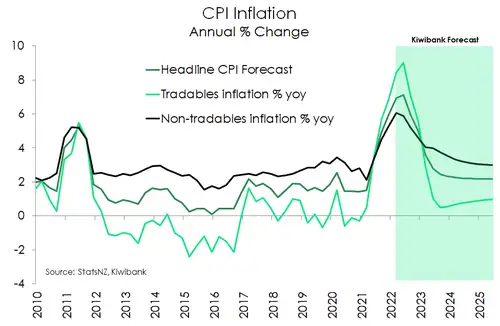

Linking a downgraded outlook and rapidly rising interest rates, is the strongest inflation seen in a generation. Inflation hit 6.9% in the March quarter – the highest rate in almost 32 years. It’s easy to forget that Inflation was only 1.5% just a year earlier.

The sheer pace of the surge in inflation has eroded real incomes, stretched budgets, and shocked the RB to unwind pandemic era stimulus double time. And we don’t believe CPI inflation has peaked. We’re picking inflation to hit 7.1% in the June quarter.

Contributing to the acceleration in cost-of-living is the broad-based nature of the current rise. Tradables (or imported inflation) has been propelled higher this year because of supply-side shocks. These shocks include a jump in commodity prices such as oil because of the war in Ukraine. And global supply-chain disruption has persisted as China has maintained its covid elimination strategy. Severe lockdowns in cities such as Shanghai has blocked the ready flow of goods to and from the world’s second largest economy. Domestically, the release of pent-up demand from various lockdowns and a housing market boom has stoked domestic demand and non-tradables inflation.

We see tradables inflation peaking at 9% in the June quarter despite the Government’s fuel excise tax cuts. Barring another major supply-side shock, we expect imported inflation to fall sharply into next year. Despite peaking at a lower rate, non-tradables is a much slower ship to turn around – owing to its sticky nature. Monetary policy tightening is predicted to eventually bring domestic inflation to heel. Given the current distance above the top of the RB’s 1-3% target band CPI inflation is forecast to still be above 3% early next year. But inflation should return to the target band from mid next year.

The housing market has already responded…

Rising interest rates are already bringing the housing market to heel. House sales are down around 30% on a year ago. And house price growth has tumbled since peaking late last year. Credit conditions have tightened in a large part due to rising mortgage rates. But other policy changes have had a hand in turning many away from housing. Policy changes such as new tax rules for investors, CCCFA changes to bank due diligence requirements, and tighter deposit requirements. We continue to forecast that house prices will fall 10-11% by the end of this year before a muted recovery from late 2023.

Others see house prices falling by more, and that is a distinct possibility. However, the labour market – with a record low unemployment rate – is expected to continue cushioning households (both mortgage holders and renters) from a nasty income shock. NZ still has a housing shortage, albeit drastically reduced while the border was closed, and new supply is being delayed. Material and labour shortages plague the construction sector. In addition, much of the new housing being built is infill housing which usually requires the demolition of older stock. As a result, the net increase in NZ’s housing stock is not likely to be as dramatic as current record high building consents data imply.

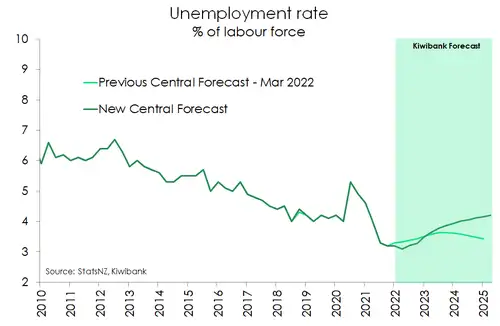

…and the labour market will in time

Easing demand translates into a rising unemployment rate ahead. However, the acute labour shortages currently present are likely to persist for some time. As a result, the unemployment rate is forecast to gradually rise over the next few years. And by gradual we mean the unemployment rate is not likely to reach 4% until mid-2024. The re-opening of the border will eventually help to ease labour shortages by lifting the supply of workers. However, the delayed opening of the border to non-visa waiver countries until July is not expected to see a strong recovery in long-term arrivals until much later in the year. Meanwhile, we are forecasting a sizable net migration outflow this year.

Rising labour costs are at the heart of ongoing domestic inflation pressure. The very tight labour market, exacerbated by a closed border, has seen a notable increase in pay rates. Job switching is rising as employers offer higher pay to poach workers. Other employers have had to lift pay for existing staff in order to limit the number jumping ship. And over the year ahead there is likely to be some very heated pay negotiations that will be expected to cover the rapid rise in the cost of living. Wage growth, which typically lag movements of the broader economy, is forecast to steadily rise to a peak of 4% by early next year. A rate not seen in StatsNZ’s private sector labour cost index.

Beware of the inverted curve

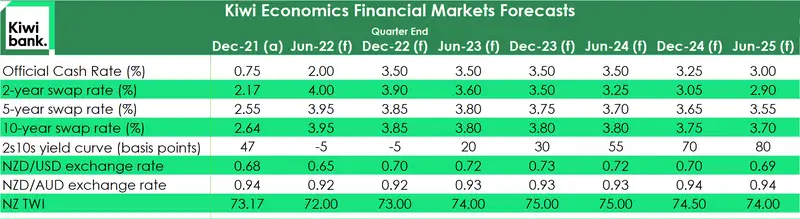

The RBNZ have outlined a tightening in policy, unseen in the post-GFC (2008) period. Interest rates are headed into ‘restrictive territory’ and will restrain economic growth further.

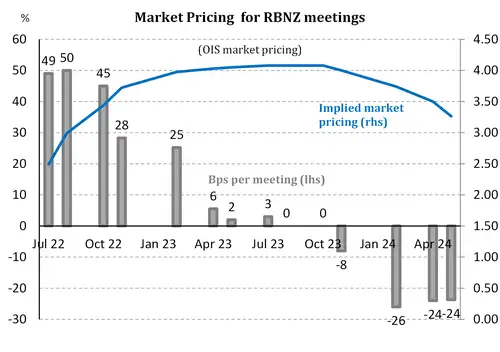

Yet the RBNZ continues to forecast a soft landing. Although the pace of tightening is fast and furious and unforgiving. The market’s pricing for future RBNZ policy decisions is illustrated in the chart below. The market has (effectively) 3 x 50bps moves in July, August and Oct – taking the cash rate to 3.5%. There’s another 28bps in November – taking the cash rate to at least 3.75%. Into 2023 the pace of tightening fades, but the cash rate peaks at over 4% (in line with the RBNZ forecast). Late in 2023, the market is entertaining the chance of rate cuts. Because it is widely expected that a move to 4% would induce a hard landing. A hard landing is basically a soft landing without breaks, a helmet or a mouthguard.

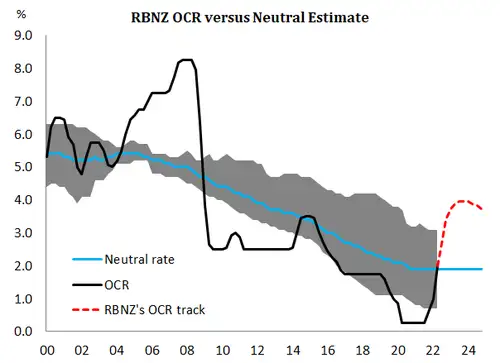

Our next chart illustrates the ‘neutral’ (neither restrictive nor stimulatory) cash rate – blue line – and the actual cash rate – black line. The RBNZ’s proposed policy moves – the OCR track – is highlighted with the red dotted line. We are currently at neutral (2%) and the RBNZ has forecast a continued hiking of the cash rate to 4%. If delivered, Aotearoa will face the tightest monetary policy settings since 2008. And of course, the risk of recession rises with every rate rise from here. We don’t see the cash rate heading to 4%. We believe the RBNZ will get enough bang for buck going to 3.5%. In the meantime, the curve may invert under pressure.

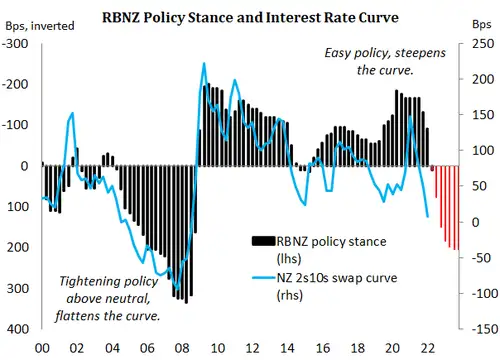

Our next chart illustrates the policy stance (restrictive versus stimulatory) and the shape of the Kiwi swap curve (2-year versus 10-year swap rate spread). Since 2009, monetary policy in Aotearoa has been broadly stimulatory. Policy was only returned to neutral briefly in 2014. The shape of the Kiwi rates curve is largely driven by monetary policy (expectations).

When monetary policy is loosened to stimulate growth, short term interest rates fall as the cash rate is slashed. And longer-term interest rates hold up or actually rise as higher growth and inflation is expected, as a result of policy stimulus. The curve is said to steepen. Conversely, when interest rates are hiked to tighten policy, short term rates rise at a fast clip than longer term rates. And the further tightening goes, the greater the reduction in future growth and inflation expectations, which pulls down longer-term rates. The curve is said to flatten.

Since the RBNZ started hiking, the Kiwi swap curve has flattened. The more the RBNZ tightens, by hiking the cash rate, the more the Kiwi curve will flatten, and invert. An inverted curve, with long-term rates lower than short-term rates, is a signal that a recession may be on the horizon.

The RBNZ’s move into restrictive territory is well underway. Mortgage rates have already lifted materially in anticipation. We expect the RBNZ’s policy action to keep a flattening bias on the Kiwi curve as the risk of recession rises with every rate rise. The “inversion signal” from financial markets may grow stronger in coming months and quarters.

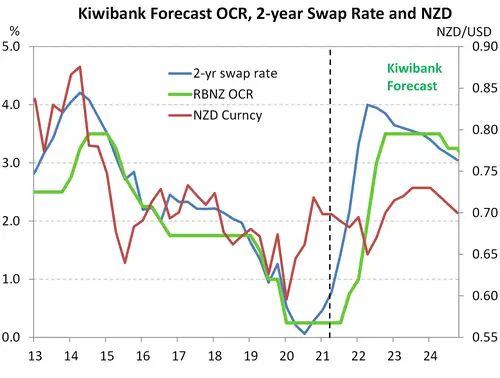

The Kiwi currency has been under significant downward pressure. The NZD had hit a low of 0.62c against the Greenback in mid-May.

The decline in the Kiwi was overdone. The Kiwi then staged a comeback, to push towards 66c in late May. And now the Kiwi is under downward pressure again, heading towards 0.62c again. Although we forecast a stronger Kiwi dollar by year end – ending around 71c – we expect to see a great deal of volatility.

All content is general commentary, research and information only and isn’t financial or investment advice. This information doesn’t take into account your objectives, financial situation or needs, and its contents shouldn’t be relied on or used as a basis for entering into any products described in it. The views expressed are those of the authors and are based on information reasonably believed but not warranted to be or remain correct. Any views or information, while given in good faith, aren’t necessarily the views of Kiwibank Limited and are given with an express disclaimer of responsibility. Except where contrary to law, Kiwibank and its related entities aren’t liable for the information and no right of action shall arise or can be taken against any of the authors, Kiwibank Limited or its employees either directly or indirectly as a result of any views expressed from this information.